- Home

- Valerie Trueblood

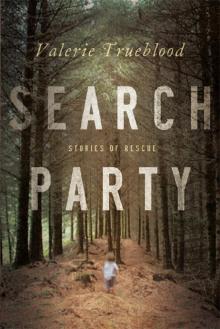

Search Party

Search Party Read online

Search Party

Valerie Trueblood

SEARCH

STORIES OF RESCUE

PARTY

COUNTERPOINT PRESS

BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA

Copyright © 2013 Valerie Trueblood

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

The author thanks the publications where some of these stories first appeared: One Story, “The Magic Pebble”; Wordsmitten, “Street of Dreams”; Thresholds (UK), “The Llamas”; Seattle Review, “The Finding.”

These stories are works of fiction. The events and characters in them are products of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events or to persons living or dead is coincidental.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Trueblood, Valerie.

[Short stories. Selections]

Search party : stories / Valerie Trueblood.

pages cm

“Distributed by Publishers Group West”—T.p. verso.

ISBN 978-1-61902-223-2

I. Title.

PS3620.R84S43 2013

813'.6—dc232013002369

Cover design by Faceout Studios

Interior design by David Bullen

Counterpoint Press

1919 Fifth Street

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10987654321

Contents

The Finding

The Magic Pebble

Downward Dog

The Llamas

Think Not Bitterly of Me

The Mouse

Guatemala

The Stabbed Boy

The Blue Grotto

Later or Never

Street of Dreams

Who Is He That Will Harm You

Search Party

He said, “If a story begins with finding,

it must end with searching.”

Penelope Fitzgerald, The Blue Flower

SEARCH

STORIES OF RESCUE

PARTY

The Finding

THIS is how my new life came about.

It started with symptoms I thought might be neurological. As a nurse, I was alert to a new unfamiliarity in the way things looked, as if I kept finding myself on the wrong street, or as if I were traveling abroad. The stores of what was ordinary enough to be ignorable seemed to be shrinking. Sometimes I seemed to inhabit my body the way you stand on a foot that has been asleep.

It may be that the organs attempt, in a language we do not know, to give us tidings of their dim world. Or with secret promptings they may impel us to ends of their own.

I had never visited this practice before, but I had worked in the same hospital with the neurologist long ago. He had been someone I knew to say hello to, a well-liked man, a good doctor, married, though without children and said to be unlucky in his home life.

On the morning of my appointment I got up and looked out at the rain. Water was materializing on the windowsill, filmy and soundless. It was December so I put on a red sweater over my uniform. I took a bus from work in the afternoon, and in the neurologist’s waiting room, which was empty, I sat up straight to give the nurse the understanding that I was not demoralized by the winter rains of our city, the slow or the steady, or the short daylight. I was not a depressed woman drawing myself up to the radiator of a doctor’s attention. If anything I was unnaturally cheerful. I wanted to seize whole tortes from cabinets in the bakery, and bottles of wine from under people’s arms, and sofas out of window displays, that I had no room for in my small house.

In the clinic, there was no one in sight except the short young girl with a triangular face at the desk behind the glass, who had slid me a clipboard of forms with her bitten fingernails. When she saw me looking at her half-inch-long hair she turned away and touched it with her fingers. Well, hair is that short! I thought. Where have I been?

After a few minutes she looked up sharply and said, “Just go through the door. Room three.”

From the hallway came a heavy sigh, a groan, actually, just before the doctor knocked. Then his voice, very deep—I remembered the voice—sounded from the door. “My nurse is not here,” he said. “In a moment Angelique will come in so that I can examine you.” He was fifty or so now, with big pale flap ears, and neatly dressed, tall but not erect. He had the stoop of a person with a bad back, and the eyes in folds that I recalled from seeing him in the hospital years ago. Now that I was older I knew these were drinker’s eyes. “My nurse called and said she would not be in. She quit. No notice. There are no charts set out, as you see. No X-rays. She simply quit.” He appeared only half able to think, like a man who has been up all night.

“I am a nurse,” I said, waiting for him to recognize me, although I had been younger and prettier at the time I worked in that hospital.

“I see that,” he said, scanning the clipboard.

“I used to work down the hall from you at the university,” I said, pointing to my name on the form, and then to my employer’s name, to let him know I was not in search of a job.

“Is that so?” he said.

Angelique opened the door without knocking. “What if the phone rings while I’m in here?” she demanded, putting her foot in the wastebasket to stomp down its contents.

“We might empty that,” the doctor said, avoiding her gaze. She ignored him. Hey there! I signaled him with an older-generation smile. Better establish some authority with this girl!

She did get down in front of the examining table and grapple on her knees with a step, which she yanked out for me to mount. I settled myself on the padded table surrounded with metal trees holding instruments. “If you’re not going to have her disrobe,” said Angelique, “I don’t need to be here, do I?” and she went out, shutting the door firmly behind her.

The man looked blankly at the ophthalmoscope in his hand. Finally he switched it on and began to peer at my retinas, changing his angle minutely again and again, and breathing as if his belt were too tight. After a while he said, “I am going to have to dilate your eyes. I have not been brought up to date on your problems.” He glanced at my forms. “You are a new patient. And you were not referred.”

“No,” I said. “I came straight to you.”

“Headache,” he said wearily.

“No,” I said. I described my symptoms while he put drops in my eyes. After a while he hunched over them again. At length I submitted half-blind to all the tests with pin and hammer, of reflex, balance, strength, and mentation, naming the year, the city where we lived, the president. It was at the mention of the president that our eyes met. This was some years ago. I could tell we felt the same despairing way about the man. “I am going to ask you to have an MRI. There is only one real finding, and it may be nothing. But we will take a look.” He stood up and pressed his wide waist, stifling a deep, trembling yawn.

“I agree,” I said. It was not like me not to ask what the finding was.

“Are you planning to stay?” he asked Angelique rather cautiously as we passed her cubicle.

“I have to study my Spanish. You don’t remember, but my exam is tonight, so there’s no point in going home. So I’ll close up!” She swiveled the chair so her back was to us.

“Well, then. I will leave now,” he said, “to pick up some things. Good night.”

It was dusk but the sun had come out, producing that low-lying light that seems to be coming from below rather than above. The air was full of water.

You could hear water slipping over the edges of the grates in the parking lot. On the steps he said, “Now I remember you. Urology.”

“Cardiology,” I said.

“Well, I have business to attend to.” He smiled unpleasantly, as if I had detained him. “My wife, soon to be my ex-wife, has my dog. I am going to get her. The dog.” He searched his pockets.

“Where does your wife live?” I said.

“Where indeed. In her house by the lake.”

“I wonder if you could give me a ride. I can’t see. I do have a car, but I came on the bus. I ride the bus when I want to think.”

“Well, if you have left off thinking for the day,” he said, opening the door of his car. He performed a tight turn to get out of the parking lot, with the tires splashing.

I did not get out at the corner where I could have walked home; I had decided not to. Instead I asked him about the dog. This worked a change in him; his face lit up with malice. He began to talk. His wife was bent, it seemed, on punishing faults in him that he did not name, and would not give him his dog, even though she disliked dogs and had not the slightest notion how to take care of them. She might have changed the locks to keep him out. She thought he wanted to get into the house and make off with things he had bought for her, when in fact he was perfectly happy to have left everything behind; he didn’t care even to go near the house again, except for the dog. The dog was his. His deep voice had become a snarl; he shook his shoulders and said, “Where exactly may I drop you off?”

I said, “Oh, we’ve passed the place.” He had been talking, growling, for blocks. “I might as well go with you to pick up the dog, and get out on the way back.” He replied with his groaning sigh.

The house was hidden from the street by a dense laurel hedge. It was dark now but not raining, and if you turned back at the top of the steep walk you saw a drop-off with the dark lake spread out below, so unexpected it could have sprung right out of a rock.

A weightless feeling comes over me whenever I look down on water from high up on land. Seeing it I felt a certainty that I was not sick, I was well. Instead of the sensation of being subtly awry I had the feeling I was in the midst of a normal life.

But now I was very hungry. This looked like the sort of house where fruit would be set out in a bowl from which you could help yourself.

The locks had not been changed after all. In the front hall there was no bowl of fruit but a crystal dish of sourballs. I stopped to take a cherry one, and he grimly swept the whole lot into his pocket. I unwrapped mine and dropped the paper on the floor. He offered no apologies for the size of the house or the fussy luxury of its furnishings, but made straight for the kitchen in the back.

Sure enough there was a dog, asleep in the shut-up kitchen without even a rug. It was a damaged version of a collie dog, thin, with an awful coat, and it scrambled up guiltily when we opened the kitchen door, like an old man pretending he hadn’t been asleep in his chair. The dog had a smell, a putrid steam, which came up and surrounded us. When it began an agonized wagging and scooting toward him, he fell to his knees.

He knelt and pardoned the dog’s appearance and smell and used a voice to convince it it was something besides these things, something an animal might not suspect itself to be. And he picked it up. It should have weighed too much for that but it didn’t. Without speaking, he indicated the keys he had put down on the counter. I locked the door behind us, and he lugged the dog down the steps and through the hedge, eased it into the back seat, and got in with it. I thought he was going to get back out but he kept stroking and soothing the dog, which was panting unhealthily.

I had the keys. I got into the driver’s seat. Nothing happened so I started the car. I said, “You can’t take a dog like that into a downtown hotel, now can you.” He didn’t answer; he was in a reverie petting the awful-smelling dog, like a schoolboy with his thoughts in his hands. In the rearview mirror I could see them both with their eyes shut.

“So if I took him to my house,” I said after a while, “you would have to come every day to take care of him.”

“Her. She’ll die without me. Look how sick she is now. Good dog. Good dog.” He sat for blocks stroking the dog, as the fumes from its coat rose and banked in the car.

“In that case you would have to come with her,” I said finally. I had seen the girl tell him what to do. I had seen the whole thing. I pushed all the buttons in the fancy armrest to open the windows. By now it was dark and cold, and the cold air, still wet, whirled in the car. The dog raised its nose to sniff.

He said, “I would have to get my things.”

I turned to go downtown, where the hotel was. After a time he said, “Some of my things are at the office. I shuttle back and forth.” So I doubled back. When he got out of the car the dog shut its eyes again, hopelessly. We hurried in. Angelique was alone, tilted back in the chair in her cubicle, studying her Spanish book. She had her shoes off and there was a run in her tights.

“Well, look who’s here,” she said in a lonely voice. “I heard you in the hall. I hoped it was you and not a rapist.” I looked down at her. For all her rudeness she was a hopeful girl, thinly dressed below the funny hair, and ill-fed. With some care she could be the daughter I never had.

The Magic Pebble

THE flight to Lourdes was open to the whole archdiocese. Huge widebody, full. I was in the middle of coach in a row of five, in the middle seat.

All right, I’ll make the best of it. I have my little Sony, I’ll turn it on when they say we can and talk to two people, and that will be the program: me, the dressed-up old fellow on my left, and the woman on my right with a nun in charge of stuffing her bag into the overhead bin and getting the seat belt out from under her. At first I thought the woman was blind but she was just slow, in a daze. The nun had a broad pink face, heavily and dramatically wrinkled considering its resigned expression.

I have become aware of resignation in others. By the time you reach the third chemo, one of the things you notice is that the people around you accept death, your death. It happened with my radio show; during my last sick leave, friends from the station kept telling me how well the show was doing on reruns, how I didn’t need to feel I had to hurry back to it.

I’m back, though. Now I can ask for anything. My boss Charlie always did give me free rein, but the station manager has taken to sending me complimentary memos not unlike greeting cards. To the manager’s way of thinking, according to Charlie, my illness drops a fringed scarf over the rummage-sale nature of the show, lends it a dimly glowing aura of the endangered, the soon-to-be-archival: items veined and burnished and distressed now, like fake antiques, by my attention. As for me, I have finished with the disappearance of the tiger and the frog from the earth, and with the university hospital where patients were secretly injected with plutonium. Away with reproach. On to Inventions and Patents! The Sightings of the Ark! Birds in History!

If you write a noun, any noun, on a piece of paper and slap it down on Charlie’s desk he grins, the radio snaps on in his mind. He remembers “satellite” new on everyone’s lips. He is happy with his throwback job; he’s a gray-haired, loping man who could easily have a beer with the campus agitator he was thirty years ago; he has his own tattered copy of the Port Huron Statement. He remembers “pacification,” newborn “fluorocarbon,” reborn “terrorist.” He charts the passage of world figures in the press, from “madman” to “strongman” to “leader.”

“I’m beyond all that. I’ve given up,” I tell Charlie.

“OK,” he says.

“I’m going for the fun factual or the seriously miraculous.”

“OK.”

This trip I am taking springs directly out of The Song of Bernadette.

By the time we made our high school graduation retreat the decline in vocations was serious and the hopeful sisters were showing this movie. How beautiful and good the curious tapered face of Jennifer Jones was, so sad-mouthed, in that movie. Even so, we snickered at he

r dull wits, her inability to speak up for herself when she was the one, after all, to whom Our Lady had stepped out of rock, clothed in white and a blue beyond blue, with yellow roses on her feet—as we seniors of Holy Names knew despite the black-and-white of the movie. No human: a statue come to life, shining with unearthly glamour, melting with bridal politeness. An invisible power filled the air but the girl could not stretch out her hands to determine the source of it. Much was offered, but touch remained in the realm of the unpermitted.

“From the remotest times, out of child-sacrifice to water, out of rainmaking and ceremonial cleansing, from sacred well, holy pool, fountain in oak tree—the spring has been thought to possess a miraculous power.”

For music maybe somebody blowing into a bottle.

“Unorthodox”—or maybe I should say “orthodox”—“as such a trip seemed when it first occurred to me at the end of chemo, I saw it as something that would perhaps . . .” “Perhaps” is a little clothespin not really sturdy enough, I’m afraid, for the vast wet sheet of the possible that I have to hang from it. Halfway through I’ll break in with passages from novels, pro and con. “That world of hallucinated believers,” Zola called Lourdes—which won’t be my position; I won’t presume to judge. At the station they’ll say, “This was her best show, she left her shtick at home, she was honest for a change.” Because they know I’m always feigning interest. Even when it’s one of my causes, in which I have the most intense interest privately, I slip into this broadminded radio-interest. Whereas the mark of real interest would be silence, like that preserved by my boss Charlie at my bedside. “Saline infusion,” I’ll read him, “followed by the nitrogen mustard . . .” He’ll wrinkle his forehead, squint, and then I’ll laugh and he’ll laugh. I can tell he would like to do a show on chemo.

My husband, with his inborn, unfailing sense of the thing to say to a person in chemo with tufts of her former self in her hands, says irritably, “What’s so funny all the time? He’s got a crush on you. Charlie. I’m serious, he does.”

Criminals

Criminals Seven Loves

Seven Loves Search Party

Search Party Marry or Burn

Marry or Burn